Episode Summary

On this episode, we are discussing something that's been a part of our lives as far back as we both can remember. It's influenced the way we dress, the way we talk, the music we listen to. It's what makes us who we are. In 2023, we're celebrating 50 years of this culture that we call hip hop. We were originally gonna do just one episode, but realized that this conversation might take a little longer than usual, so part 2 will be dropping in a few weeks.

Transcript

Miguel: Hi kids. Do you like fun?

Christina: Yeah.

Miguel: And bookmarking a bunch of articles you'll probably never read? We're starting a monthly newsletter called Liner Notes. We'll be sharing what we're watching, what we're listening to, throwback YouTube videos, updates on our upcoming projects, random shit you may have missed on the internets, you know, stuff like that. The link is in the show notes or you can go to troypodcast.com/newsletter. Do it.

Christina: Now.

Miguel: It's good for you.

Christina: It'll make your teeth whiter.

Miguel: [Laughs] And back to the show.

—

Christina: This is They Reminisce Over You. I'm Christina.

Miguel: And I'm Miguel. On this episode, we are discussing something that's been a part of our lives as far back as we both can remember. It's influenced the way we dress, the way we talk, the music we listen to. It's what makes us who we are. In 2023, we're celebrating 50 years of this culture that we call hip hop.

Christina: [mimics air horns]

Miguel: There are few things in this world that we can point to and say, this is where it started. And hip hop is one of those things, and that's what we're gonna be talking about on this episode. All right, so, you just want to get started now?

Christina: Let's do it.

Miguel: So, in the late '60s and early '70s, when we watch archival footage of New York City from those times...

Christina: It's wild.

Miguel: It is, it looks like war torn countries.

Christina: Yeah, like, the buildings are literally crumbling.

Miguel: Yeah. Burned out buildings. They look like they've been in a battle.

Christina: And the kids are just jumping on old mattresses outside on like, piles of crumble.

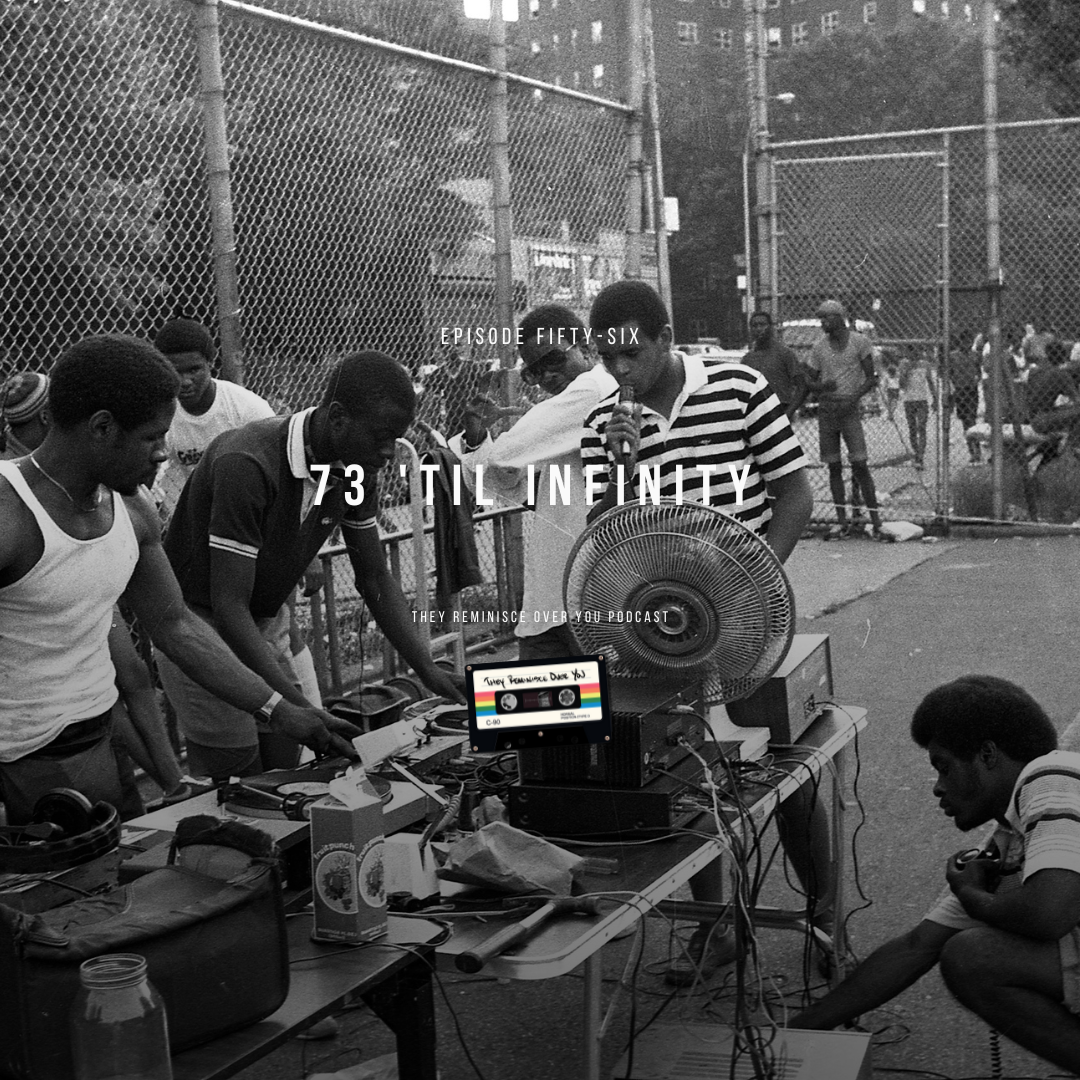

Miguel: Playing on burned out cars. And that's what New York, specifically the Bronx, was like in those days. And you had DJs who were not able to work in the clubs in Manhattan, but they were doing smaller parties in, in the Bronx. So, they would be doing little local clubs, rec centers, doing things at parks.

Most of 'em were playing disco music because that was what was hot at the time. One DJ by the name of Clive Campbell, aka Kool Herc, he was a DJ who played funk and soul music. And for years, this is what he's doing. He's like, the man in his neighborhood in the Bronx, this little section of the Bronx, where he was like, the DJ. He went to, or he took a style from the clubs in Manhattan where they would have two turntables going at one time, so you could seamlessly go from one song to the next. But what he was doing is using these two turntables to try and loop some of the songs that he was playing.

Christina: Okay.

Miguel: He hadn't done it publicly yet, but he had the idea to create what he called the "Merry-Go-Round" style, which is funny to hear it called something so silly as the "Merry-Go-Round" style.

Christina: Makes sense though.

Miguel: It does, because he noticed that when he would play like, these James Brown songs, when it got to the break, people would just go nuts and just start going crazy on the dance floor. So, he figured, why not loop these two records together and just extend the break? So, you have a ten second break in a song. People go nuts. I can stretch it out for a minute by going back and forth with the two records, and he decided that he was gonna try this out at a back to school party that he was throwing for his sister. He told them upfront, look, I'm trying something different tonight. I don't know if y'all gonna like it, but I'm gonna try it anyway. And basically spent the entire evening playing breaks.[1] He's looping all of these breaks. People are going crazy, dancing and whatnot.

Christina: Break. Dancing. A break for dancing.

Miguel: Yes. That's essentially what it is. And that happened on August 11th, 1973. It was the catalyst of what would become hip hop music.

Christina: So...the breaks were born, I guess this DJ style...

Miguel: Yeah. The "Merry-Go-Round" style.

Christina: Which birthed break dancing.

Miguel: Yes.

Christina: Then, how do we get to "rhythmic" speaking? Aka rap?

Miguel: Well, the rap portion of it was the last thing to to happen in terms of this hip hop thing.

Christina: Okay.

Miguel: Basically, while DJs are hosting their parties and doing whatnot, they're shouting people out. They're giving information on where the next party is gonna be. They're just letting you know what song is playing, things like that. Eventually, there were some DJs who just strictly wanted to DJ. So, you would get your boy to do it. Somebody who had the gift of gab—

Christina: The MC.

Miguel: Who could, who would be the Master of Ceremonies, aka, the MC, who could keep the party moving. So, you would hand him the mic and now he's doing all of this stuff. He's telling you about who's gonna come to the party next week, or where it's gonna be and how great your DJ is over here. Show him some love. And as more people started to do this, of course, you know, you get a little arrogant with it. Like, my DJ's better than yours. I'm better than you at whatever you're doing over there. Can't nobody talk shit like I do. Look at my clothes. I'm pretty, I can dance. I got all the girls and it just started to become like, more rhythmic with it.

I believe the guy's name was Coke La Rock[2] was the first person to do this, and it just spread from him. Kind of the same thing with Herc. He was the first person to take this style and loop the the breaks. But other DJs started to emulate that, and then they would add on top of it.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: So, you have Grand Wizzard Theodore, who created the scratching.[3] You have Grandmaster Flash, who took Theodore scratching techniques and added to it and just kept adding more and more layers on it. And it was the same thing with the, MC-ing. People just talking shit and elevating it as time progressed.

Christina: Okay, so this is the late '70s.

Miguel: Not yet. This is still—

Christina: Oh, we're still in...?

Miguel: Yeah, this is still '73, '74, '75. Like, this is taking a while for it to catch on. It's really only in the Bronx at this point, although a few things have leaked out to other neighborhoods. But for the most part, everything's concentrated in the Bronx.

Christina: Yeah. You know, it's funny, um, we always talk about how like early '90s rap was very regional and stuff, but when you look at the early history of the beginnings of hip hop, we think of New York as like, the birth of hip hop. But the boroughs were very regional too.

Miguel: Yeah.

Christina: You know, when we watch these interviews and documentaries and stuff, people will be like, if you live in Brooklyn, like going to Harlem was like, a trek. Like, you don't like, the boroughs were very self-contained.

Miguel: Yeah. And—

Christina: And they all had like, their own styles and, stuff too. And as we'll see later, the boroughs will kind of, they will each like, battle with each other and whatnot.

Miguel: And at this point, if you're not going to the Bronx to go to these parties, you don't know it exists. There are a few people in the other boroughs who do know about it because of course, people being who they are, they were recording all of these things and selling the tapes on the side.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: So, if you didn't have a tape or you weren't there when it happened, you don't know this shit exists and eventually it starts to get out to other boroughs and people are performing it in the parks and it took a couple years for it to get citywide. And that's when we get to the, the late 70s. '78, '79, once people have started to put their crews together, uh, they are full on rapping at this point. People are putting their routines together. You've got dancers. So, it became a production. And of course with hip hop being what it is, everybody wanted to be better than the next group.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: And that's what hip hop was built upon. So, the early pioneers, the three who were looked at as the godfathers of hip hop, Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash.

Christina: Yes.

Miguel: Bambaataa was the leader of the biggest gang in the Bronx. He was like, the most feared dude on the block. He was the leader of the Black Spades and just—why are you laughing?

Christina: I don't know. It just sounds funny.

Miguel: And essentially he was a gang leader.

Christina: Mm-hmm.

Miguel: He got tired of getting harassed by the police. A friend of his was killed by the police and he's like, look, I need to find something else to do with my time other than just running this gang. He goes to a party, hears Herc play, and was like, I got some of those records at the house. I can do this. So, saved up some money. Got some equipment. Now he's DJ-ing. He took his crew the Black Spades and was like, look, we ain't doing this gang shit no more.

Christina: Just like that?

Miguel: Just like that. We're gonna be on this positivity.

Christina: Okay.

Miguel: We, we're about to turn over a new leaf and we're gonna give back to the community. We're going to throw these parties, and we are now known as the Zulu Nation.[4] So, they had a built-in fan base just by being a gang.

Christina: So, they were like influencers of their time.

Miguel: Yeah, pretty much. The DJs were the influencers. So, now you've got Herc and his crew on one side of town. Bambaataa and his crew on the other side of the Bronx. You got Flash and his crew coming together wherever he was, and they're all pushing the culture forward and everybody's starting to get a taste of it. So, by the time the late seventies rolls around, that's when people are like, you know what? We can make some money off this. We need to make some records.

Christina: So, we're kind of at the point where there are people who really like it and they're thinking this can be something. We're also getting to the point where more people wanna make records, but "the powers that be" are saying, hmm, I don't know. Is it gonna stay? What is this? Is it a fad? Do people like this?

Miguel: And you also have it, like I said, expanding outside of the Bronx, finally. So, you have people like Fab Five Freddy, who's a graffiti artist hanging out with the Keith Harings and the Basquiats of the world. And they're going to these clubs in Manhattan and hanging out with like, Debbie Harry from Blondie.

Christina: Right. Who—

Miguel: Which is putting them in touch with the the hip hop crowd, and now she's referring to Fab Five Freddy and Grandmaster Flash on their song "Rapture."[5]

Christina: Doing her little rap.

Miguel: Yeah, so I saw a few interviews with people who were around at the time, and as they're starting to make their way out of the Bronx and go downtown, they're hanging out in the punk scene. So, you got these hip hop dudes coming from the Bronx hanging out with the girl with the pink mohawk in the club downtown, and they're all like, enjoying the same shit.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: Uh, Jazzy Jay said that it was weird at first, but after a while it's like, you know what? They're kind of cool. So—

Christina: I mean, I would imagine you have the experience of being sort of like on the fringes. Even if you're on, maybe you're different fringes, but you have the experience of like, hey, we're different.

Miguel: Yeah. And they're all hanging out together at these clubs now. And that's exposing it to more [whispers] white people.

Christina: Aka mainstream. Mainstream.

Miguel: It's becoming a a lot more mainstream, at least in New York City. So, it's starting to actually become a thing now. And once "Rapture" goes to number one on the charts, now it's starting to break out a little more nationwide. Like, what is this and who is this white girl doing it?

Christina: When, when did that come out?

Miguel: That was '81[6], I wanna say 1981, '82. Somewhere in there.

Christina: All right. I'll take your word for it.

Miguel: Don't take my word for it. Look it up.

Christina: I don't wanna type right now and make clicking noises. We can always add it to our footnotes later.

Miguel: Exactly.

Christina: Well, I was just asking what year, because I was actually looking up MTV's refusal to play well, Black music in general for a while. They barely wanted to play Michael Jackson. Forget rap music. But then of course when you look up this stuff, you're gonna stumble on David Bowie, very politely, and I say politely in quotes, criticizing MTV for not playing Black artists.[7]

He was being interviewed by one of the first VJs, Mark Goodman. And he's trying to make all these excuses about like, middle America might be scared if they see Prince. And David Bowie would be like, hmm, that's interesting. But he wouldn't let him make any of his excuses, but he was just like, hmm, all right, all right. You can go ahead and talk all that shit, but I think it's dumb.

And I just find that so weird. 'cause we're talking about how like it would start off being pretty concentrated in the Bronx, but it started to spread throughout New York period. And you got MTV that's headquartered in New York who are like, nah, we ain't playing Black—like I said, they didn't wanna play Michael Jackson until they were forced to. But then you have David Bowie, who's not even American talking about why don't you guys play Black music?

Miguel: Yeah. David was a little more polite than Rick James was. Because Rick was saying the same thing around the same time, but he was a lot more vulgar with it.[8]

Christina: Surprise, surprise.

Miguel: He was basically the opposite of everything that David Bowie was.

Christina: Well, David Bowie might have been more composed, but as one of the comments pointed out, "it's amazing how Bowie can be so calm and composed in his words while radiating disgust to this interview."

Miguel: Yeah.

Christina: 'Cause you could just see it in his face. He's like, that's interesting.

Miguel: Yeah, that little smirk said it all. Like, oh, okay.

Christina: All right. I'll let you just talk yourself in circles and I'll pretend to be nice.

Miguel: Exactly.

Christina: Half pretend to be nice. Yeah. But even then, when they finally started playing Michael Jackson, it wasn't like they were going straight to rap. It was still like, you know, pop, R&B.

Miguel: Yeah, and the only reason they played Michael Jackson is the record label threatened to take all of their artists away from MTV.

Christina: I read one of these historical accounts and the MTV, I dunno, CEO, whatever at the time, claims that they played it on their own accord, but I don't believe them.

Miguel: Me neither. Me neither.

Christina: Because, um, another retelling that I read was, as you were saying, the head of CBS records said you're gonna play "Billie Jean" or you're not gonna play anything. And they dragged their heels still and didn't play it until "Billie Jean" hit number one on Billboard.

Miguel: 'Cause that makes all sorts of sense.

Christina: Michael...he was on the cusp of becoming the Michael Jackson, but he was still popular.

Miguel: Yeah. And had been popular for 15 years at this point.

Christina: Right. And then not only that, after him releasing "Thriller" that just changed music videos, period. So can you imagine if they continued not playing Michael Jackson? Then they would've missed out on "Thriller."

Miguel: Exactly.

Christina: Anyway, so yeah. If Michael Jackson had to have the head of his record company fight for him, these little rap music videos weren't gonna make it to MTV for a little while.

Miguel: Yeah, it was a couple more years before that happened. There were a few more songs that came out in between this time and before they started to play it on MTV, like "Planet Rock" was another big one that kind of put together the electronic music with the hip hop music you had "The Message" by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five that had come out.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: And that kinda shifted the style of music for the first time. Prior to that, everything was, Hey, let's have a party. Let's have fun. Let's have a good time. And "The Message" is like, yeah, this beat is dope, but we gonna talk about how bad New York City is. Like, all the bad stuff we see when we walk outside, "Broken glass everywhere. People pissing on the stairs, it's like they just don't care." They weren't doing that before that record.

Christina: Yeah. I guess when you're coming off like, the disco wave, you're gonna have party music.

Miguel: Yeah. And not only that, you—

Christina: And then it started as a party thing.

Miguel: Yeah, it started as party music because you're trying to get away from "people pissing on the stairs, it's like they just don't care." So, you looking for some escapism at that point, but it got to this song and it is like, you know what? Let's kind of dial it back a little bit and talk about what's really going on and not this fantasy world that we wanna live in. So, you got people telling stories about where they're from, the things that are going on in the neighborhood. They're still dressing like weirdos.

Christina: Yeah.

Miguel: As they're telling these stories, but the music itself is starting to change.

Christina: Dressing like disco cowboys.

Miguel: Yeah, you got people with headdresses on, glittery, sequins...

Christina: Leather pants and boots.

Miguel: Mesh tank tops, all of that. But around this time is when you start to see The Run-D.M.C.'s and the LL Cool J's, it, it's funny that Melle Mel, and those guys before that are considered old school and Run-D.M.C. is new school, and that's from like, 45 years ago. That's considered new school. But they were the new wave. They were the new hot thing. They were the younger kids. Even though the Melle Mel's of the world were like, 22, 23 at the time. You got these 18 year olds coming out and saying, hey, this is what we're about. Like, we can do this too, but we don't wear these funny ass costumes.

Christina: Well, and that's probably why it adds to why it feels like it's so old, because you have like, old school and new school and we're still in the '80s.

Miguel: Yeah. This is '83, '84 and we're talking about old school. Which is wild to think about, but this is around the time, like I said, you got Run-D.M.C., you got Ice-T doing his thing in L.A., Schoolly D in Philly, and these are all people who are no longer dressing like The Furious Five. The reasons that Dre and Yella got made fun of with the World Class Wreckin' Cru, is they had on sequined doctors scrubs.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: So, people were starting to, to move away from that in this era, and it kind of turns away from people just performing in the parks and in the clubs and just making singles. And now people are actually starting to make albums.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: Because at this point, actually, I'm just gonna read the list down to you. In 1979, how many hip hop albums do you think were made?

Christina: Well, I have a list too.

Miguel: Okay.

Christina: Well, I was gonna mention, I don't know if you saw it, but Wikipedia has, uh, a whole list, list of years in hip hop music[9]. So, every year they have a list of every album that was released.

Miguel: Yep.

Christina: Is that what you're looking at?

Miguel: No, I wasn't looking at that, but I have another list that shows how many were released every year.

Christina: I don't know how many, but I looked at 1979 and then some of the '80s, and you could easily scroll down the page. And then it looked at 2023 and it was just like, one month was probably equal to like a whole year.

Miguel: Yeah, so, in 1979 there were zero albums recorded and 38 singles.

Christina: All right.

Miguel: 1980, three albums. '81, two albums. '82, twelve. '83, thirteen. '84, seventeen and '85, thirty-two.

Christina: What? 32?

Miguel: Yes. A whole 32 albums. I did the same count for 2023. As we're recording this, today is August 3rd, 2023. There have been 389 hip hop albums released since January 1st.

Christina: And when you say albums released, I'm assuming these are like through record companies and more official means. This probably doesn't count all these people on their, you know, YouTube releases and SoundClouds and whatnots. Right?

Miguel: 389 through the first seven months of 2023.

Christina: And I will probably know two of them.

Miguel: Meanwhile, in the first like,15 years of hip hop, you had about 420. But anyway.

Christina: Yeah.

Miguel: This is what we're looking at in the early to mid-80s is now people are starting to make albums versus just having singles out. And because there are so few albums being released, that means that there's not a lot of rappers that we know. Like, publicly on a nationwide scale, all of those local rappers back in New York, there's probably hundreds of them, but nationwide, we only know like 10 to 15 of them, if that.

Christina: And sometimes just by name.

Miguel: Yeah, there's a lot of them that we only know by name.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: So, that's why in those days it's lot easier for us to say, you know what? This is good and this is bad. We like this. We don't like that. And even though there weren't very many of these albums coming out, a lot of it was pretty good for the time. Unlike today, where you got 389 coming out in half a year. How many of those are actually good?

Christina: Or worth listening to a whole album.

Miguel: Versus just singles. But hey, what did I know? I'm just an old dude. So, yeah, there was a total of 79 albums—

Christina: Shut up old head!

Miguel: Yeah, basically. A total of 79 albums that were released between 1979 and 1985. Video Music Box[10] was a show that was based in New York. It was a public access show that was playing a lot of the videos that MTV wasn't gonna gonna play. So, all of the stuff that couldn't get on MTV. MTV's refusing to play it. Video Music Box filled that gap.

Christina: And that was only in New York. Right?

Miguel: It was a, a local public access channel that Ralph McDaniels started his show on in 1984.

Christina: Yeah, I remember when we were watching the documentary about it, I kept getting it mixed up with The Box.[11]

Miguel: Yeah, that's completely different.

Christina: So— it is, I was like, when are they gonna start talking about you being able to make requests?

Miguel: Yeah, that's something—

Christina: And I was like, oh wait, this is something different.

Miguel: Yeah. Not the same thing. Something completely different. At that point, the only place you're really gonna get your, your hip hop is some radio stations would play an hour a week on a Friday, where you get to hear all 12 hip hop songs that came out this year or whatever.

Christina: Right.

Miguel: Uh, so you would hear it Friday or Saturday night.

Miguel: Friday Night Videos[12] was a show that came on at like, midnight on NBC. For an hour, so, you might get one rap video in a sea of pop. Occasionally you would get a couple on MTV, but not many people had MTV at this time. Like, I know we didn't have it at home. I would see it when I went to my aunt's house. But at home we didn't have cable, so, I wasn't seeing it there. But it, it started to grow a little bit after this point. It was when Run-D.M.C. did the "Rock Box" video and the "King of Rock" video. It had a lot of guitar in it.

Christina: So...

Miguel: It kind of appealed to the sensibilities of the execs at MTV. So now you've got the suburban kids seeing Run-D.M.C. all across America, and that's kind of exposing it a little bit more.

Christina: Right. When I was looking through the Wikipedia list of all the hip hop albums I was trying to look at what year do I think that I started to, to get into it. ‘Cause I think there's a lot of older songs that I discovered later. And so I think for me, which makes sense, 'cause this is basically the start of the Golden Era, was 1986. I feel like that's maybe when I dipped a pinky toe into the water. It's possible I could have just discovered some of these songs later.

But some songs are getting more mainstream attention, which is probably how I started to hear it, like Salt-N-Pepa "Push It." "Walk This Way" with Run-D.M.C. and Jazzy Jeff and The Fresh Prince. So, those songs, I'm like, okay, I remember hearing these songs and as we talked before in a previous episode, how I was accidentally introduced to N.W.A., but I was not ready for them yet. And plus I had started listening to some R&B, like Janet Jackson and Jody Watley and stuff. So, I think I was kind of like primed for it.

But '89 I think for me was my entry point, which makes sense because I was looking up when Rap City on MuchMusic here in Canada started and that started in 1989[13]. So, I guess that kind of makes sense with getting more exposure, 'cause at this point, I remember Tone Loc, "Funky Cold Medina," "Wild Thing." Like, those were songs that I liked, not just songs I kind of heard in passing. These are songs that I liked. Young MC "Bust A Move." And then Maestro Fresh Wes, who I didn't realize was Canadian at the time, ‘cause I think I wasn't really thinking about like Canadian artists, American artists, but Maestro Fresh Wes had "Let Your Backbone Slide." So, that makes sense knowing that Rap City started that same year because even though it was only a 30 minute show once a week, now I had a chance to see it more.

Miguel: Yeah, for me it goes all the way back to '79. Even though I was only four years old, I remember hearing "Rapper's Delight" because my aunt had the, the single. So, just hearing that around the house or some Kurtis Blow that one of my cousins had. So, I was hearing these songs and now that I think about it, it's like, how in the hell did this stuff make it out to California?

Christina: Right.

Miguel: Especially that early.

Christina: Well, I think that, that other documentary[14] we're watching about the mixtapes kind of really showed how, the music moved.

Miguel: Yeah. And it was pretty quickly too. But I'm just surprised that it would make it all the way to California and we were able to hear it on the radio and buy it in stores at that point. So, I'm hearing all of those songs.

I vividly remember, oh, this is so funny, at least to me. Being in the car with my mom and one of our cousins came to pick us up. They're like the same age, so, they were probably 25-ish, 26 at the time. And, "The Message" is playing on the radio and you know how the hook goes, "Don't push me, ‘cause I'm close to the edge," all of that. I remember my mom talking about my dad and saying that if he did something, that's what she was gonna have to say to him. To not push her 'cause she's close to the edge. And I will never forget that. I was sitting in the backseat. I was like, yeah, I want to hear her say that. I can't wait for her to say that to him. I don't know if she ever did, but I remember that conversation vividly. Me just sitting in the backseat, cheesing like, yeah, you tell him Jeannette!

Christina: I feel like she did.

Miguel: Probably. I'm sure she did, but that's one of—

Christina: Or something close to it.

Miguel: That's one of my earliest hip hop memories was her planning to quote that to my dad.

Christina: Yeah.

Miguel: I'm gonna have to ask her if she actually ever did it. But yeah, as the, the music started to grow and more and more albums and more and more rappers were coming out, it was just something that drew me in and I was always hooked and into it.

Christina: Well, by 1990 I was, all in. When I looked at the '89 stuff, there were, it was just a handful of songs. But by 1990, I still didn't know a lot, but now there were artists and albums that I liked. Like Hammer, Please Hammer Don't Hurt ‘Em. Like, all those singles, Salt-N-Pepa, all those singles. LL. Mama Said Knock You Out. I actually had those, like, I don't know if—were CDs available yet, CDs or tapes.

Miguel: They were.

Christina: And Bell Biv Devoe, technically not rap, but they're hip hop.

Miguel: They were hip hop adjacent.

Christina: Hip hop... What was it? "Smoothed out on the R&B tip."

Miguel: Yeah. It was the same for me at that point. I wasn't listening to anything else because as you know, I'm very anti-Luther Vandross, even though I'm a fan of Luther Vandross at this time, I was like, man, I don't wanna hear that shit. So, Luther Vandross, Freddie Jackson, all of that stuff I wanted nothing to do with it.

And there was a couple radio stations in LA that only played R&B. And I mentioned several times on this show how we had 1580 KDAY, which was the first all hip hop station anywhere. So I'm assuming that—

Christina: You were spoiled.

Miguel: Yeah, I had thought every city had that. I had no idea. But there were two stations in L.A., KGFJ and KJLH. I don't remember which one it was, but one of them, part of their tagline was, "we don't play that rap." Basically like, we don't do that shit over here. Come get this Freddie Jackson. I don't remember which one of them it was, but it was one of those two stations where they were like, we ain't doing that shit over here. We play real music here.

Christina: Right. You always have the older generation who looks down on the newer generation's music.

Miguel: Yeah. And that was them. We don't do that, and then turn on like, Freddie Jackson "Rock Me Tonight," or whatever that song is. "Dance Tonight."[15]

Christina: So, it's funny that rap, hip hop was able—I mean, I guess young kids were just hungry for it, but then the music and the culture had to fight against the older generation and racism.

Miguel: Yeah. It was a battle on both fronts that they had to deal with. But probably '90, '91, '92, that was like the tipping point when it kind of fell over into the mainstream, like, fully.

Christina: Definitely.

Miguel: Because you have The Arsenio Hall Show pumping it to you. You have Yo! MTV Raps, and Rap City pushing it to you. You've got radio stations that are now starting to play it, except for KGFJ and KJLH. They would play songs that had rappers on them, but play the rap-free version. Like Jody Watley's always doing a record with a rapper on it. You never heard those verses on KJLH, but this is when it really hit the mainstream. So, you got rappers doing movies and TV shows. MC Hammer had a goddamn cartoon.[16] So, it was starting to get huge and that was probably the biggest moment for, I would say Black music. Because you not only had hip hop, but you had new jack swing was really big. House music was really big at the time. You had reggae coming back, so a lot of dancehall artists, a lot of hip hop influenced dancehall artists were out coming around this time as well. So, it was just a big time for Black music.

Christina: Yeah. And then the emergence of hip hop also being fused with the R&B artists that were coming up at the time, like Jodeci and Mary J. Blige brought in like, a new R&B sound too.

Miguel: So it, it was a good time for people like me who loved hip hop, but still always had to fight to protect it. Your teacher's like, "you shouldn't listen to that. It's gonna rot your brain." Like, shut up, Mr. So-and-so, you don't know what you're talking about. I did have one teacher that would let us listen to it in the classroom though, so, he was cool.

Christina: So, this is like '91, '92. This whole period of like, '86 to '97 is, there's some debate, but give or take a year or two, that's like "Golden Era."

Miguel: Yes.

Christina: But within this "Golden Era" are like sub eras.

Miguel: Yeah.

Christina: Because the late '80s, early '90s, you're kind of like coming off of new jack swing and party music and stuff. And then we get to the early 90s, there's a change. We went from a lot of party music, fun stuff. You know, we always say how like in the '90s we were so hopeful, like it's the '90s, you know, things are gonna be different. But then we get to like, '93 and it's like, hmm, maybe shit ain't so sweet after all. So, between like '93 and '95, like, to me that's like, another wave. Because that's when we get Nas, Wu-Tang, OutKast, Snoop, like, all this stuff. Things get a little gritty again.

Miguel: Yeah. And that basically comes from like, the L.A. influence because you have N.W.A. and Ice-T doing quote unquote gangsta rap. And that kind of drove what hip hop was coming into, and it also came with a lot of pushback. Just out of nowhere you had jealous ass Tim Dog doing "Fuck Compton." Like, it's N.W.A. and DJ Quik's fault that you can't get a record deal? Be better instead of just being wack like you were.

Christina: Yeah.

Miguel: So, he's out here taking shots at them. You have magazines when they're doing reviews, giving west coast artists lower scores. Some New York artists talking slick in some interviews that they're doing about how west coast music ain't quote unquote real hip hop. There was a lot of that going on. Just haters basically.

Christina: I think, um, and this is something that just popped into my head. This is just my theory, but maybe too with it growing, in popularity, maybe some of these rappers started to feel like, hey, there's something I wanna talk about and I want people to hear it. Like you were saying with the first wave, it was like, it isn't just all parties and stuff. There's people pissing in the stairwells, right? I think that probably added to it where it's like, sure, we like to party and stuff, but there's other stuff going on and I want to—"the south got something to say!"

Miguel: Yeah. Like, everybody had something to say.

Christina: Something to say. And now it's like spreading more again, throughout other cities and stuff, and they're like, we got something to say too.

Miguel: Yeah, everybody wanted their shot. And they were starting to get it. So, the New Yorkers were just trying to hold onto it. Like, no, this is ours. And if you're not from here, you suck.

Christina: Which led to the the wild ass '95 Source Awards.

Miguel: Yeah. So, you, you start with Tim Dog saying what he said about Compton. And you have artists like Ice Cube and Westside Connection saying, fuck what these critics gotta say. "Hip hop started in the west!" [17] He knew, he knew that some shit was going to come up when he said that. Because you got New Yorkers blaming the downfall of hip hop on west coast artists. You got Common doing "I Used To Love H.E.R."

Christina: Yes. Now she went to the west coast and what did he say? And now she wants to do the gangsta rap something...I forgot all the words now.

Miguel: Something about "hanging out with gangsta bitches."

Christina: Oh yeah.

Miguel: Like, he has something positive to say about everything except the west coast.

Christina: Except the west coast. Yeah.

Miguel: So, it was just a lot of that that was building up. Then you get to the, the Source Awards. Well, right before that, you get Tupac getting shot. And even though he said that it was not an east and west thing, it had to do with him and Bad Boy, people still took that shit and ran with it. Coming to the Source Awards, this shit just comes to a head where you got Suge talking about Diddy, "If you want to be a star and stay a star, come to Death Row."

Christina: "All up in the videos."

Miguel: And Diddy pretending that he's not instigating anything, but yet saying, "I live in the East and I'm gonna die in the East," but I'm not instigating anything at all.

Christina: Then you got all these other ones, who are just like, I just came here to perform like 69 Boyz.

Miguel: They just want to get out here and do the "Tootsee Roll." And so the Source Awards was, what did, uh, Questlove say? He was like, "the night that hip hop died"[18] or something. I'm not gonna go that far and say it was that bad.

Christina: Yeah. More like the night he thought he might die if he didn't leave since he's running out of the auditorium and accidentally stumbling into a D'Angelo demo. So, it worked out for him.

Miguel: So, I won't say it was that bad, but it was still a tense time.

Christina: It was, uh, a moment in time.

Miguel: Yeah. And probably all could have been avoided.

Christina: Mmm hmm. Too many egos.

Miguel: Yeah, it was a, a lot of unnecessary ego.

Christina: Egos and people fanning the flames.

Miguel: Yeah. But something I really did like about the quote unquote Golden Era is there was something for everybody. You could listen to Arrested Development and have that followed up with an Ice Cube video or song played on the radio. And it didn't sound weird. You could have, Queen Latifah screaming, "give me body!" on a house record. And then follow that up with like, some Wu-Tang and it didn't sound weird.

Christina: You had the choice to listen to all of it, or just the stuff that you liked.

Miguel: Yeah, and I liked all of it. I don't think there was—very few rappers around this time that I would look at and be like, oh, that dude is terrible. Or she sucks. But for the, the most part, it's like, whatever mood I'm in, there's something for me to listen to. If I wanna hear something funny, some punchlines, I can throw on some Redman. If I want to hear some "How I Could Just Kill A Man," I can throw on some Cypress Hill.

Christina: You wanna put your elbows up to some, some Snoop.

Miguel: There was something for everybody, and that is what the Golden Era was. It was enough for everybody. There was a lot to enjoy.

Christina: Well, I think something that, obviously we didn't know at the time because they were new, but it birthed a lot of people who are still important today.

Miguel: And that leads us to what ended the "Golden Era." Unfortunately it was due to tragedy with all of the east coast and west coast issues. Tupac getting killed in '96 and then Biggie in '97. And even though hip hop was still growing at the time, those two moments kind of put a damper on everything. And at the same time, because things are still starting to grow, it's about to become bigger than it's ever been, shortly after this. Leading us into what most people call as the "Bling, Bling Era."

Christina: So, once corporate money and just...capitalism comes into play, things change a little bit. I mean, people were making money then too, but not like this.

Miguel: Yeah. It was, you might wanna say, it was still pure. It hadn't been corrupted too much yet.

Christina: Yeah. As much as it had reached mainstream appeal, I mean, you had me listening to it out in Abbotsford, so, it wasn't exactly a secret anymore. But there was still some...I don't, I hate saying the word authenticity 'cause I don't wanna sound like those weirdos. Like, uh, you don't know the good stuff. But there was still something, yeah, I guess like you were saying, pure, authenticity, something raw and like, untouched about it.

Miguel: Yeah.

Christina: It wasn't like, it didn't feel like they were making music for the masses. Yeah. So, I think after this period is where things started to be like, oh, this is gonna make money, let's make a hit. I think there's that fine line between wanting success and just wanting to make a hit.

Miguel: What I always found funny during this time, like late '80s, early '90s, is how quick people were saying, you're a sellout.

Christina: Yes!

Miguel: You made a pop record. Like, the whole point is to make records that are popular. Just say you don't like this person, not because they're a sellout or anything.

Christina: Yeah.

Miguel: Most likely, they were talking about MC Hammer.

Christina: Yes.

Miguel: And Kid-N-Play and stuff like that.

Miguel: Like, the goal is to sell records. You don't want to sell 30,000 copies and make no money and nobody listen to your records. The whole idea is to make records that people want to hear. You got rappers like EPMD doing a song called "Crossover." "We strictly underground funk, keep the crossover." Like, you should want to crossover whether you do it purposely or it happens organically. That should have been the goal is to get your music into the hands of as many people as possible instead of trying to keep it all to yourself.

Christina: See, I think again, it's the fine line, right? People can't discern the difference between your music crossing over because people like it, or your music crossing over because you're bending to the masses.

Miguel: Yeah.

Christina: Which is two different things, but some people will look at it as like, oh, well you got popular, you're a sellout. Because now even looking back at all, the criticism that Hammer got it's like, but he just made like really good fun music and he had lots of dancing and stage presence and stuff. So it's like, how can you not like it, right? Like, how is that his fault for being entertaining?

Miguel: I think that's where Hammer messed up is he didn't push back against it. He should have just said, y'all can kiss my Black ass. I'm gonna go over here and dance and keep making these hit records. But Hammer decided, you know what? I'm no longer an MC. I'm bigger than that. I'm an entertainer. I'm just gonna be Hammer from now on. I'm not gonna be MC Hammer. That was a mistake on his part as well.

Christina: Yeah, I think I was just about to say that I think that what he started out as was fine, but maybe that's where that fine line gets crossed, where it's like, what, what was the original purpose?

Miguel: Yeah, because I don't see much difference from his first couple albums to "Can't Touch This." Like it's still a heavy sample. He didn't have bars to begin with, so, that, that wasn't his appeal. He, he was gonna give you something to dance to and he's gonna bounce around on stage for an hour. But I think he should have just said, y'all can go to hell. I'm gonna keep dancing my ass off. And if you don't like it, so what.

Christina: But people liked it.

Miguel: They did. I liked Hammer. I'll openly admit that I still know some of those routines from some of his videos.

Christina: Definitely. Me too.

Miguel: But I would still listen to N.W.A. and didn't think Hammer was a sucker though. Like, uh, Andre 3000 would say, "run up on Hammer."[19]

Christina: Yes.

Miguel: "He'll whoop your ass." Oh man. So on that note, I think we're gonna wrap up this first portion of our #HipHop50 episode. Is there anything you want to add, talking from 1979 through the "Golden Era" that you want the the people to know?

Christina: I'm glad I was there for it, even though I was in my own sort of little world. I didn't get to experience it in New York where it started, but I got to experience it firsthand.

Miguel: You did.

Christina: So, that's not the same as these kids longing for the days of the 90s by watching videos on YouTube, so I can be a little like, hmmpf, I was there.

Miguel: Exactly. Exactly. All right, so I think we should just go ahead and get on outta here. Uh, like I said, we will be putting up part two of this episode, not the next episode, but the one following. So, one month from now, you'll be hearing part two of this discussion of our 50 years of hip hop.

Christina: Yeah, we originally gonna do one episode, but realized, uhhh, this might take a little longer than usual.

Miguel: And we didn't even talk about everything in this episode. There's a lot of stuff that we didn't even come close to touching on. We got like 10% of it.

Christina: Yeah, but this isn't, uh, a hip hop 50 podcast, so, we're gonna do our best to get it out in two episodes.

Miguel: Yes. On that note, we outta here.

Christina: Bye.

Miguel: Bye.